How Do You Know if Fenantyl Is in Your Drugs

- Research

- Open Admission

- Published:

Perspectives on rapid fentanyl test strips as a damage reduction practice among young adults who use drugs: a qualitative study

Harm Reduction Periodical book 16, Article number:3 (2019) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

In 2016, drug overdose deaths exceeded 64,000 in the United States, driven by a sixfold increment in deaths attributable to illicitly manufactured fentanyl. Rapid fentanyl test strips (FTS), used to detect fentanyl in illicit drugs, may help inform people who use drugs most their risk of fentanyl exposure prior to consumption. This qualitative report assessed perceptions of FTS amidst young adults.

Methods

From May to September 2017, we recruited a convenience sample of 93 young adults in Rhode Island (age 18–35 years) with self-reported drug use in the past thirty days to participate in a pilot study aimed at better agreement perspectives of using take-dwelling house FTS for personal utilize. Participants completed a baseline quantitative survey, and then completed a training to larn how to use the FTS. Participants then received ten FTS for personal use and were asked to return 2–4 weeks after to complete a brief quantitative and structured qualitative interview. Interviews were transcribed, coded, and double coded in NVivo (Version 11).

Results

Of the 81 (87%) participants who returned for follow-up, the majority (n = 62, 77%) used at least one FTS, and of those, a majority institute them to be useful and straightforward to use. Positive FTS results led some participants to alter their drug apply behaviors, including discarding their drug supply, using with someone else, and keeping naloxone nearby. Participants also reported giving FTS to friends who they felt were at loftier risk for fentanyl exposure.

Conclusion

These findings provide important perspectives on the employ of FTS among young adults who use drugs. Given the loftier level of acceptability and behavioral changes reported by study participants, FTS may be a useful harm reduction intervention to reduce fentanyl overdose run a risk amidst this population.

Trial registration

The study protocol is registered with the US National Library of Medicine, Identifier NCT03373825, 12/24/2017, registered retrospectively. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/bear witness/NCT03373825?id=NCT03373825&rank=1

Introduction

Opioid overdose is an ongoing public health crisis in the United States (U.s.), exacerbated by fatal overdoses involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl (herein referred to equally "fentanyl"), a powerful synthetic opioid contaminating the North American drug supply [1, 2]. Every bit early on equally 2013, several states in the Usa, specially those in the Northeast, began to report a rise in the total number of overdose deaths attributable to fentanyl and related analogs [3, 4]. By March 2015, due to the rapid increase in fentanyl-involved overdose fatalities, the United states of america issued a nationwide alarm to police enforcement identifying the dangers and increased prevalence of fentanyl in the illicit drugs supply [3,4,5]. Between 2015 and 2016, at that place was a 21% increase in the age-adapted rate of overdose deaths in the United states, driven by a rise in deaths involving synthetic opioids, primarily that of fentanyl [6, 7]. These overdose fatality trends highlight the urgent need to address fentanyl contamination in the US drug supply and its associated harms.

The rate of fentanyl-attributable fatal overdose has been particularly high amidst residents of New England, the northeastern region of the US [eight, 9]. In 2016, fentanyl was found in 58% of all overdose deaths in Rhode Island, a land in New England with an overdose death rate near 1.5 times greater than the national average [x, 11]. Additionally, fatal opioid overdoses are affecting younger populations than previous years. In Rhode Isle, young adults have the fastest growing rate of fatal overdoses; more than one in four fatal fentanyl-related overdoses in 2016 were among people betwixt the ages of 18 and 29 years [12, 13].

When implemented finer, damage reduction interventions can reduce the rate of fatal opioid overdoses amidst people who utilise drugs [14, 15]. For example, the distribution of naloxone (an opioid antagonist that reverses the furnishings of an opioid overdose and can be easily used by laypeople) through customs- and chemist's shop-based overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND) programs has been shown to reduce opioid overdose mortality [16,17,18]. Communities with OEND programs accept shown greater reductions in overdose mortality compared to those without such programs [16, 17]. Moreover, the distribution of naloxone to laypersons has been constitute to exist cost-effective [16, 17, xix]. However, due to the increased and varying dominance of fentanyl and related analogs, naloxone doses previously adequate to reverse an opioid overdose may non be consistently sufficient [twenty]. In addition, consumption of fentanyl causes more profound respiratory depression than other opioids and produces clinically distinct symptoms (due east.yard., bradycardia, chest wall rigidity) that precipitate rapid onset of overdose death, narrowing the window of opportunity to administer naloxone [21, 22]. Due to the drug's authority, only a miniscule corporeality—the equivalent of several grains of salt—can crusade an overdose death [23] and can be nearly impossible to identify in illicit drugs with the naked center.

Rapid fentanyl test strips (FTS) stand for an emerging harm reduction intervention that may help to forbid unintentional fentanyl exposure and accidental opioid overdose. These tests have the ability to find the presence of fentanyl and some analogs in urine or in drug samples dissolved in water that are believed to be contaminated [24, 25]. Drug checking has become a staple impairment reduction intervention in parts of Europe and Canada, through the establishment of drug testing programs and supervised injection facilities (SIFs) [24, 26,27,28]. People who use drugs (PWUD) living in parts of Europe and Canada tin bring their drugs to harm reduction organizations or SIFs to accept them tested for adulteration; yet, PWUD in the US practice not have access to the aforementioned types of programs because of legal barriers to implementing SIFs at the federal level [29,30,31]. In studies of fentanyl testing washed outside of the Usa, persons who use FTS and who receive a positive examination issue may exist more likely to partake in overdose prevention strategies than a person who is not aware that their drug is contaminated with fentanyl [32, 33]. Therefore, the utilize of FTS may be an important harm reduction practice to inform and increase date in overdose prevention behaviors, employed before an overdose occurs.

In the US, where SIFs accept not been legalized, FTS offer PWUD the pick to test their own drugs in a individual setting. Considering bear witness for distributing FTS for dwelling house use by PWUD is nascent, there are many uncertainties regarding the efficacy and the safety of FTS self-testing as a means of overdose prevention [34]. Preliminary inquiry has found mixed results regarding the efficacy and acceptability of fentanyl self-testing as damage reduction strategy. A study performed in Due north Carolina among people who injected drugs institute FTS were widely used among the sample and that a positive FTS resulted in changes in drug utilize behavior [35]. Other studies conducted in Canada accept found that people who were using supervised injection facilities did not employ FTS frequently considering of commonly held perceptions that virtually drugs were fentanyl-contaminated, and therefore, participants did not need to confirm its presence [34, 36]. This alien evidence points to the fact that further enquiry is needed to understand the ways in which FTS are viewed and used by PWUD. The need for additional enquiry is particularly urgent as FTS are beingness distributed by multiple Usa damage reduction organizations and state departments of health for at-abode use [37,38,39,40,41,42]. In Rhode Isle, organizations have recently started distributing FTS as office of local overdose awareness events [43].

Despite growing involvement in fentanyl drug checking engineering science, perceptions of and attitudes towards FTS as a tool to reduce overdose risk among young PWUD take not been investigated in the US. Therefore, the aims of this study were to (i) understand perspectives on accept-home FTS among young adults (age 18–35) who employ drugs in Rhode Island and (two) determine whether positive results from the FTS led to behavioral changes in the way that people utilize drugs. Understanding the perceptions of PWUD regarding FTS can formatively assistance in the evolution and implementation of rapid fentanyl testing programs in the US and in other settings experiencing a high brunt of fentanyl-involved overdose.

Methods

Participant recruitment

From May to September 2017, immature PWUD were invited to participate in a airplane pilot study designed to understand perceptions of take-habitation FTS amidst young adults who use drugs. For this study, eligibility criteria were informed past a recent investigation of fentanyl-involved overdose deaths in Rhode Island [13]. Specific eligibility criteria included (1) existence 18–35 years of historic period; (two) currently living in Rhode Island; (3) being able to speak English language; (iv) reporting the use of heroin, cocaine, purchasing prescription pills on the street, or injecting any drug in the last 30 days prior to study enrollment written report; and (five) being able to provide informed consent. Many of the participants were recruited from online classifieds (i.e., Craigslist) which discussed the eligibility criteria for our study, and by give-and-take of mouth from peers who participated in the study. Additionally, fliers were placed in public areas where PWUD are known to congregate, such as bus stations, transit centers, and local universities. This study was approved past the Brownish University Institutional Review Board (#1612001662). The study's protocol is also documented on ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier NCT03373825).

Intervention protocol

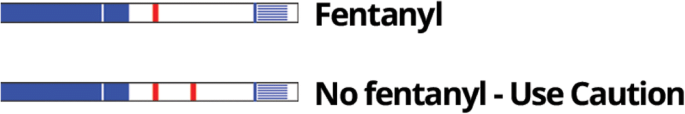

At the initial baseline visit, all consenting participants completed an 60 minutes-long survey, performed by trained research assistants, which collected information on participant demographics (such equally race, gender, age, educational attainment, housing and employment status), drug utilise patterns, and overdose history. The protocol for the initial baseline visit has been described in item elsewhere [44]. Once the survey was completed, participants were shown ii cursory instructional videos demonstrating how to apply and interpret BTNX Inc. Rapid Response™ Fentanyl Test Strips [45]. These FTS are dispensable, unmarried-utilize immunoassay tests with a detection level of 20 mg/ml; the tests provide a binary upshot of either positive or negative for the presence of fentanyl. The tests have loftier sensitivity and specificity for detecting fentanyl and some analogs [46]. Further, all participants were given a handout that was written in obviously language and discussed how to test urine or powdered drugs and pills with the FTS. Additionally, we placed a key on each of the FTS packages to help with interpretation of the exam results (Fig. 1. Fentanyl rapid test strip results label).

Fentanyl rapid test strip results label. This is the fundamental that was placed on each of the FTS packages to assist with estimation of the examination results. This primal shows that a strip with one ruby line indicates a positive test and a strip with ii red lines indicates that the exam is negative, but that the participant should notwithstanding use caution

From May 2017 to mid-July 2017, the first xl participants were instructed to use the FTS to test their urine (after drug use). We instructed participants in this offset group to use the FTS in their urine in concordance with how the production is intended to exist used [25, 45]. During the recruitment period, a dissever study found that the FTS retained loftier specificity and sensitivity when used to exam drug remainder from numberless, spoons, or pills crushed in water [46]; therefore, the study protocol was amended to instruct the 2d group of participants to test a drug sample or drug residual dissolved in h2o (prior to consumption) [46]. Participants recruited betwixt mid-July 2017 and September 2017 were thus trained to test a drug sample or their drug remainder (before consumption). In both groups, participants were instructed that a negative FTS did not necessarily indicate an absenteeism of fentanyl contaminants or zero overdose chance and were instructed to always utilise their drugs with caution. Participants were provided with overdose education and naloxone following the FTS training. This didactics also included training on how to use drugs more safely (such as using with someone else, having naloxone, and using a smaller initial dose). Once the grooming was consummate, participants were after asked if they felt comfy using and interpreting FTS independently or had whatever concerns regarding the previously described training materials and were so given ten BTNX Rapid Response™ Fentanyl Testing Strips for personal utilize.

Data collection

At each participant'south follow-upwardly visit, occurring approximately two to 4 weeks after baseline enrollment, consenting participants completed a cursory, researcher-administered quantitative survey, every bit well as a structured qualitative interview designed to capture attitudes regarding FTS apply. Interviews were conducted by trained research assistants and were recorded for subsequent transcription. Enquiry assistants had a guide of 12 open-ended questions that explored participants' test use and feel. The questions explored FTS use and full general opinions of the tests past asking, "Did you use any of the tests?" and "How was that experience for you?". Additionally, questions, such as "What was non useful near the fentanyl tests?", "What got in the way of using the tests?", and "Is there anything that would make it easier to use the test?", brought forth discussions about barriers to FTS use. The prompt, "Based on the test strip results, did you do annihilation differently when it came to how you used your drugs?", elicited discussions regarding behavior alter as a upshot of FTS use. Qualitative interviews lasted between 10 and 20 min. Participants were paid $25 after their initial visit and $fifty after completing the follow-upward visit.

Information analysis

Interviews were transcribed past four members of the research team. The data analysis was performed by using a thematic analytic approach, an iterative process of repeatedly analyzing information in order to recognize categories that subsequently get the themes of a research report [47]. For this study, a deductive approach was utilized in order to develop an initial coding scheme, which was synthetic from the interview template [48]. A code book was so developed and refined every bit new ideas and themes were discovered in the transcripts. Later on, an inductive arroyo was utilized, which brought forth new concepts and themes from the reading of the interview transcript [49]. A final coding template was created and agreed upon. Six interviews were cross-coded by ii research team members to ensure a concordance with a kappa of at least 80%. Cross-coding occurred to prevent bias and to ensure uniform use of the coding template by the ii coders. Descriptive statistics of the population were drawn from responses to the baseline researcher-administered survey. NVivo (version 11) was utilized for qualitative data retrieval and direction.

Results

Of 93 recruited participants, 81 (87%) returned for follow-up and were included in this analysis. A summary of the participant characteristics is shown in Table 1. The mean historic period was 26 (SD = 4.vii), 45 (55.5%) were male person, and the majority (n = 45, 55%) identified every bit white. Over half of the participants (n = 55, 68%) expressed concern about their drugs being contaminated with fentanyl at baseline.

Of those who used at least one FTS, 37% reported regular heroin apply, 24% reported regular cocaine use, thirteen% reported regular non-medical prescription pills use, 47% reported lifetime injection drug use, and l% received at least one positive FTS result (Table 2). A greater percentage of those who were in the urine testing group reported cocaine use compared to those in the residue testing group (49% vs. 24%); otherwise, few baseline characteristics differed between these two groups. Additionally, about half of the participants from each group who received a positive exam upshot reported altering the manner they utilise drugs. Compared to the residuum testing grouping, a greater proportion of those in the urine testing group reported irresolute their behavior following a positive FTS (62% vs. 38%); all the same, there were no pregnant differences in the specific behaviors that people reported irresolute between groups. A further quantitative analysis measuring the employ of FTS among this sample has been detailed elsewhere [50].

Overall, the majority of participants who used FTS expressed positive opinions regarding the utility and simplicity of the tests. Five key themes emerge from the interviews: (1) FTS were a tool to ostend suspicions of fentanyl cariosity, (two) differences in ease of FTS testing depended on testing method, (3) participants re-distributed tests to people with high perceived overdose adventure, (iv) participants preferred testing their drugs in individual, and (five) presence of fentanyl led to cocky-reported behavior change.

FTS were a tool to confirm suspicions of fentanyl adulteration

In general, participants expressed positive opinions regarding FTS, stating that they were easy to employ and that they provided valuable information regarding the presence or absence of fentanyl in a drug sample. Respondents stated that the FTS were useful particularly when a drug supply source was not trusted past the participants.

Everything was useful. Those tests opened my optics, and information technology has saved my life, and I can gladly say I oasis't taken any more than because I was going to take two bags. If I had took those ii bags, I think I wasn't even going to be here right now (Respondent 39, male of non-disclosed race, age 28, residual testing group).

One respondent proceeded to not use his drugs because of fright of overdose. Similar other respondents, cognition of fentanyl adulteration led to fentanyl avoidance.

But it'south (fentanyl) going to show up in the test, then it is kind of worth it. That'due south what I'm saying is, you could save your life past using this. Or you could not utilize it and do what yous're going to do and be dead...I thought it came out positive, then I got rid of the fentanyl (Respondent 17, white male, age xx, urine testing group).

Some other respondent provides an example of how he used FTS to avoid consuming of fentanyl adulterated drugs.

I contacted a local dealer of mine that I had gone to in the past, that I had mentioned earlier, I was similar questionable of his product, then I told him that I had these strips and that I was going to test, to test his stuff for fentanyl to run across if it was practiced or not and showed him the positive result… with those tests, I was able to do that with a couple other dealers between at present and then to root out my chances of getting a tainted product (Respondent 54, White male, historic period 23, residue testing group ).

This participant, forth with others, discussed how some dealers were unaware or non-forthcoming regarding fentanyl cariosity. The participant also suggested that he sought out dealers whose drugs were non contaminated with fentanyl.

Differences in ease of FTS testing depended on testing method

When prompted about barriers to using FTS, participants from both testing groups expressed that using the FTS were "straightforward" and "easy to exercise." A majority of participants expressed positive opinions of the accessibility of FTS utilise.

They're very useful, very straightforward, very simple. I retrieve it'southward a not bad tool, I think they should be given out on a street corner (Respondent xi, white male, age 29, urine testing group).

I mean the packaging was easy, I mean it'due south pretty discreet…they weren't inconvenient, they weren't hard to utilise, they weren't, yous know, embarrassing to be seen with or anything (Respondent 36, white female, historic period 34, balance testing group).

Another participant reported FTS to be easy to use and discussed showing others how to use FTS.

It was easy, you know, very easy to do in forepart of them. Very piece of cake to explain. When I say in front of them, I mean the dealers or whoever I was sourcing the product from... It was piece of cake to practise information technology in forepart of them, show them how it works, evidence them that it's constructive even with just the residue in the baggie (Respondent 54, white male, age 23, residue testing group).

Participants in the urine grouping expressed wanting to exist able to exam their drugs ahead of time in order to prevent an overdose.

If there was a like test strip yous know that you could mix a bit of your heroin, or what you think is heroin in water and dip the strip in it, and something like that, you know, like to be able to test information technology before you use it. Because, y'all know, subsequently information technology could be too late, you know (Respondent 13, male person of non-disclosed race, historic period 22).

In improver to wanting to use FTS earlier drug apply, several participants alluded to the fact that using a urine-based exam was non convenient.

I didn't have to pee all the time and so like, sometimes when I wanted to have it I would only have to beverage a bunch of water but, information technology worked out (Respondent 27, female person of an unspecified race, age 25, urine testing grouping).

Participants distributed tests to people with high perceived overdose risk

Some participants from both groups described engaging in "secondary distribution" of FTS, that is, the distribution of FTS to people in the participant's networks, such as friends, family members, and coincidental acquaintances who they perceived as having a college run a risk for using a drug contaminated with fentanyl:

I gave them to close friends of mine who I suspect still use and coincidental friends of mine...and you know I just wanted them to know, 'hey listen, yous can test if information technology's fentanyl with this, I don't know if it's a practiced thing or a bad thing, but you lot can exam' (Respondent x, black male, age 30, urine testing grouping).

Well one of my one of my aunts has, I don't come across her very much, only I know that she's had like a history with addiction, then I figured I give her one and just allow her know well-nigh what it does pretty much (Respondent 59, white female, age 22, balance testing group).

Another participant described handing out 5–half dozen of her test strips to people she knew from the methadone dispensary, who had previously mentioned wanting to know if fentanyl was in their drug supply.

They were not but shut friends, but a couple of people I met at the clinic and stuff, and they actually were people who actually want to know if the fentanyl is actually in the drugs they are using, and they really use a little scrap more than than I do. On a daily basis they still apply, so I felt like information technology was very of import to have (Respondent 55, white female person, age 28, residue testing group).

Participants preferred testing their drugs in private

When participants were asked how it felt to test their drugs at home, followed by questions that assessed their willingness to become to a local wellness organization to go their drugs tested, a majority of participants expressed that they preferred to use FTS at home. Participants reported ii primary reasons for wanting to test at habitation. Some reported they would rather use drug tests at dwelling house in order to avoid feeling judged by others.

I retrieve that people like to examination their own stuff in private. I accept friends that would get the drug test kits from the stores and just test in private because like a lot of stigma fastened to things. So when yous go to a place where you have to do drug testing even the people there can kinda look at you kinda weird um no affair what their reason is (Respondent two, multiracial female person, historic period 29, urine testing grouping).

In addition to reports of feeling judged or stigmatized, other participants suggested fearfulness of legal ramifications or other risks if they were to test their drugs someplace other than their home.

I would rather be at dwelling house. I wouldn't want to be taking my drugs into somewhere, and it'southward just like, a lot of people would experience that style too, considering like I know damn well that I'thou nothing. I'm but a statistic. Just a lot of people think that they would go to jail I'thou sure if they went to a place and they said, hey test my drugs (Respondent xi, white male, historic period 29, urine testing group).

Just because it'due south more private, it'due south in my house, I wouldn't have to risk getting caught by the police bringing information technology somewhere. I would just, I don't know, I would never bring information technology somewhere to become information technology tested honestly, never (Respondent 81, white female, age 25, residue testing group)

I feel like going to a local health system it would just be, I hate to say this, an opportunity for the cops to attempt to stop you lot as you lot're walking in to accept information technology tested. Definitely at domicile, I would definitely do it at domicile where it's more secure and I don't have to worry about anything else (Respondent 37, white female, age 28, residue testing group).

Presence of fentanyl led to behavior alter

During the qualitative interview, participants described behaviors such as using a "tester" (i.east., an initial small dose of the drug to determine potency), having naloxone nearby, using a drug with other people around, and disposing of the drug, particularly as a result of receiving a positive test. Here, participants draw how they would utilize an initial smaller dose of the drug they tested, a "test shot," in reaction to a positive FTS effect. Though this participant was not using drugs during the study menstruation, she brash a friend who was using drugs to get slower considering of the positive FTS.

A friend of mine was shooting up and before they did that I said let me test it, so I grabbed the cap after they used information technology and I tested it, and it was positive for fentanyl. And they, asked me what exactly fentanyl does and I said it'due south mode stronger than your heroin and information technology has the potential to kill you with a drib. And they were like "what am I supposed to practise" I said, honestly, you shouldn't have that, but I know y'all're going to, so accept it in portions...instead of putting the whole .4 to the face, they would do .1 at a fourth dimension, and, you know, with a fiddling flake of time in betwixt, in betwixt, each one (Respondent 68, multiracial male, historic period 21, residue testing group).

I e'er did them [FTS] with someone else. It was me and 2 of my friends a few times. And the stuff they were getting, they kept assuming it had fentanyl in it, just they weren't 100% certain. Ordinarily when heroin comes out white or articulate it's fentanyl. So, when nosotros tested it and it was positive for it, it made them, you lot know, they did a tester shot before they did the residual and that was smart on their finish considering information technology was really potent, and they would have worn out otherwise (Respondent 61, white female, age 35, residue testing group).

Another participant described how a positive FTS issue contributed to a change in her "mindset" near her drug employ and keeping naloxone nearby.

I had Narcan and I had it in the room, like I literally had it on the burrow side by side to me, cause information technology, it honestly, just similar thinking fentanyl in it was 1 thing, merely like knowing information technology was in information technology kind of like changed my, like my mindset going into it (Respondent 59, white female, age 22, residue testing grouping).

Like to other participants, another respondent described her response to a positive FTS result. She describes her conversation with her cousin, a dealer, nearly disposing of a significant amount of fentanyl-contaminated heroin.

I used one for myself, so, the other ix I gave to my cousin who is a drug dealer, um, and I told him to requite me nine samples of his dope, and I followed the video that I watched … And out of the nine that came back, seven were positive for fentanyl. So, I told him, y'all either accept seven murder charges on your record, and you have the balance of your life in prison, you don't get to run across your kids get married, graduate. Kinda requite him a fiddling guilt trip on it, merely I convinced him to flush information technology. He had almost $2000 worth of fentanyl laced heroin and he got rid of it (Respondent 68, biracial female, age 26, residue testing group).

Finally, participants who used the FTS after drug use described diverse overdose prevention strategies for the next time they used drugs following a positive FTS, including warning others about fentanyl contamination post-obit a positive FTS.

Only being able to relay, relay that information to people, that information technology actually would impact in ways that hopefully would change some of their deportment and how they conducted, either, using or, giving it to other people (Respondent 23, biracial male, age 25, urine testing group).

I would say nosotros were definitely a lot more cautious near what nosotros were doing, similar definitely a lot more ready for something to, yous know, go incorrect...I definitely, like, would pace myself a lot slower with the drugs. And you know, information technology was like I said, information technology'due south kind of lamentable to say but we were almost expecting an overdose or such. And so, if that did happen, you lot know like at least somebody could exist similar, oh and bound on information technology and human action fast (Respondent 22, white male, age 22 , urine testing group).

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that many young PWUD at risk of a fentanyl overdose perceive FTS as a feasible and acceptable harm reduction tool. In this study, we assessed 2 dissimilar applications of FTS (urine testing and residue testing) and found that rest testing is more convenient and allowed for participants to know about fentanyl adulteration before drugs are consumed. The majority of participants suggested that FTS were straightforward to use and did non cite pregnant barriers to use. Later receiving a positive test event, many participants described precautions that they believed would prevent an overdose, such as using a drug with others around, keeping naloxone nearby, or using a tester. These findings suggest FTS may represent an important damage reduction intervention for opioid overdose prevention among young developed PWUD.

While there are other methods confirming the presence of fentanyl in i's drug supply, such as the use of Raman spectroscopy and FTIR spectroscopy, prior research has establish that the BTNX Inc. Rapid Response™ Fentanyl Testing Strips take college specificity and sensitivity and are significantly less expensive than other methods [46]. Still, testing illicit drugs, through either FTS or chemic analyses, has proven to be an constructive arroyo in identifying adulterants that pose added overdose risk to PWUD, equally indicated by ongoing drug checking efforts in Canada and in European countries [24, 27].

In places where drug testing is legal, such as Canada and Europe, people who want to have their drugs tested most often need to bring their substances to specific locations. For instance, SIFs in Canada distribute FTS to their clients; however, clients must test their drugs in that same setting [51,52,53]. In Europe, drug testing largely takes place at music venues and mobile test sites with trained professionals [27, 54]. In dissimilarity, syringe service programs (SSPs) in the US are just beginning to disseminate FTS to their clients for at-home employ outside of a clinical or supervised context [40, 41]. Land governments and departments of wellness, such equally those in California, Vermont, and Maine, are also providing funding for the purchase and dispersal of have-habitation FTS through existing SSPs [37,38,39, 42]. However, there are debates every bit to whether in that location is sufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of home testing programs [32]. Given that FTS have the potential to render false negative results, PWUD using FTS may proceed to use their drugs without added precautions to prevent fentanyl overdose risk even if their drugs are contaminated with fentanyl. Exterior of monitored environments such as at SIF, a fake negative exam in a private setting could atomic number 82 to a higher risk of overdose [34]. To mitigate this concern, all participants were instructed during the FTS training that false negatives are possible and that a negative result does non necessarily mean an absence of overdose risk. Individual use of FTS (i.e., outside of monitored environments) may stand for a novel harm reduction strategy to reduce the risk of fentanyl-related overdose, even though concerns persist regarding the gamble for unintentional overdose resulting from a imitation negative [34].

Impairment reduction technologies used in private settings have entreatment to PWUD in the Usa who fear the legal ramifications and stigma associated with use of impairment reduction services, such as SSPs [55, 56]. In agreement with United states of america studies that have institute that harm reduction service tin can be uncomfortable and unapproachable for some PWUD, specially for young adults, our participants recounted their reluctance to engage in FTS use at professional agencies or harm reduction organizations [57,58,59]. Our study suggests that immature PWUD are comfy using FTS on their own and would prefer to apply them either in their ain abode or in some other private setting due to concerns for privacy and fear of abort and facing stigma from the public, institute to exist a meaning barrier to harm reduction uptake in earlier studies [58]. Furthermore, secondary distribution of FTS, mirroring documented occurrences of secondary distribution of sterile syringes, has the potential to benefit PWUD who are either uncomfortable accessing or are not closely engaged to healthcare services [60, 61]. Collectively, these findings indicate that interventions which let drug checking in private environments may potentially increment accessibility and acceptability of drug testing among young PWUD. Additionally, our participants may take used have-abode FTS equally this intervention allows for self-efficacy and peer-to-peer interaction, which take been establish to pb to successful implementation damage reduction programs in previous research [57].

Upon receiving a positive FTS result, many participants were motivated to engage in various harm reduction techniques, including using a smaller dose, having naloxone nearby, using the drug with someone else around, or disposing of their drugs entirely. Consistent with another study of FTS conducted in the U.s.a. [35], participants stated they employed these precautions because they were made enlightened of fentanyl contamination. Prior studies of cocky-testing technologies suggest similar results—that is, rapid self-testing may contribute to an increase in harm reduction behaviors. Multiple studies on rapid self-testing for HIV, a applied science that was legalized for calm utilise in the US in 2012, take reported noticeable increases in both perceptions of run a risk and target risk reduction behaviors [62,63,64,65]. Additionally, studies have shown HIV cocky-testing is a successful intervention for increasing routine HIV testing among hard to accomplish and difficult to engage populations, such equally immature adults engaging in high-risk behaviors [66, 67]. Such findings offer hope for rapid testing applied science equally a key component of damage reduction interventions for fentanyl overdose. Furthermore, in Canadian studies of FTS, and in initial studies of FTS in New York City, participants who received a positive FTS upshot inverse their beliefs in similar ways to the electric current study; they slowed downward their use, used a smaller dose, or disposed of the drug that was institute to contain fentanyl [25, 26, 42]. Given these results, FTS should be explored as an additional means of preventing opioid overdose used in tandem with other harm reduction measures, such as naloxone distribution and overdose education. In contrast, it has been hypothesized that in areas where fentanyl contamination is pervasive, PWUD who take taken drugs that contain fentanyl and take not experienced an overdose may go complacent in their employ of overdose prevention strategies [34]. This could prove to exist true in Rhode Island where participants noted that fentanyl contamination is likely. Ultimately, future enquiry is needed to evaluate FTS interventions to empathise how FTS may contribute to behavior change amongst young adults.

This study had a number of limitations. First, every bit the average follow-up fourth dimension frame was less than a calendar month, some participants did not take an opportunity to try the FTS, given that some reported a lack of opportunity to either buy or utilise the drugs in the study's timeframe. Many of the participants who had non used FTS during the written report had expressed that given a longer time frame for employ, they would have tried the FTS. Future research regarding fentanyl FTS should include a longer period betwixt the provision of the FTS and follow-up. Second, though interviews varied in length, they by and large did not terminal more than than xv min. Across this pilot projection, future studies could conduct longer interviews with participants, which may let for a more than nuanced agreement of the influence and consequence of FTS utilization on behavior change among young PWUD. Third, discussions of how drug use changed following a positive FTS effect could exist affected by social desirability bias. Additionally, choice bias may have occurred due to healthy screenee bias [68], in which PWUD who want to avoid fentanyl may be more likely to enroll in a report of FTS. Nonetheless, our results suggest that participants altered their drug beliefs as a upshot of having a definitive knowledge that their drug contained fentanyl. 4th, while nosotros ascertained that many of the participants had a history of homelessness, we did not enquire if participants faced challenges of using FTS due to current housing instability or homelessness. Therefore, we cannot make claims virtually FTS usability among those currently experiencing homelessness. Finally, this written report took place in Rhode Island, a land with a loftier burden of fentanyl-related overdoses and fentanyl contamination. As such, results may not be generalizable to other settings, particularly those in which the presence of fentanyl contamination in illicit drugs is less common.

Determination

In sum, FTS may prove to be an important harm reduction tool, peculiarly in the context of the US opioid overdose crisis, as fentanyl and fentanyl analogs are increasingly responsible for the rising charge per unit of overdose fatalities in the US [half dozen]. This study is among the beginning to explore the perceptions and employ of FTS among immature adults who use drugs. Participants expressed that FTS were an efficient and straightforward tool, and many reported distributing them to other persons in their social networks. Participants too discussed the value of FTS as a damage reduction tool for identifying fentanyl contamination and informing overdose prevention behaviors. Have abode rapid tests that take the ability to observe the presence of fentanyl and other analogs may offer PWUD boosted options for overdose prevention in the face of increasing contamination in the US drug supply.

Abbreviations

- FTS:

-

Rapid fentanyl test strips

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- OEND:

-

Overdose education and naloxone distribution

- PWUD:

-

People who utilise drugs

- SIF:

-

Supervised injection facility

- SSP:

-

Syringe service program

- US:

-

United States

References

-

Rudd RA, Aleshire Northward, Zibbell JE, Matthew Gladden R. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000–2014. Am J Transplant. 2016;xvi(4):1323–vii.

-

Gladden RM. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in constructed opioid–involved overdose deaths—27 states, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Cyberspace]. 2016; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6533a2.htm

-

Increases in fentanyl drug confiscations and fentanyl-related overdose fatalities [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 [cited 2018 Jun 7]. Available from: https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00384.asp

-

National Heroin Threat Assessment Summary [Internet]. Drug Enforcement Administration; 2015 Apr. Available from: https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2015/03/18/dea-bug-nationwide-alertfentanyl-threat-health-and-public-safety.

-

DEA issues nationwide alarm on fentanyl as threat to health and public safe [Internet]. United States Drug Enforcement Administration. 2015 [cited 2018 Jun 7]. Available from: https://www.dea.gov/divisions/hq/2015/hq031815.shtml

-

O'Donnell JK, Halpin J, Mattson CL, Goldberger BA, Gladden RM. Deaths involving fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and U-47700 - 10 states, July-December 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(43):1197–202.

-

Hedegaard H, Warner M, Minino AM. Drug overdose deaths in the United states of america, 1999-2016 [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017 December [cited 2018 Jun 7]. Report no.: NCHS data brief number 294. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db294.htm

-

Rudd RA. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2016; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm655051e1.htm

-

O'Donnell JK. Trends in deaths involving heroin and constructed opioids excluding methadone, and law enforcement drug product reports, by demography region — United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Net]. 2017 [cited 2018 Jan 26];66. Available from: https://world wide web.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6634a2.htm

-

Counterfeit prescription pills containing fentanyls: a global threat. DEA intelligence brief [Net]. US Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Assistants; 2016. Bachelor from: https://www.dea.gov/printing-releases/2016/07/22/dea-study-apocryphal-pillsfueling-us-fentanyl-and-opioid-crisis

-

Middle For Disease Control. Drug overdose decease data [Internet]. 2018 Jan [cited 2018 Jan 26]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html

-

Country of Rhode Isle Section of Health. Drug overdose deaths [Internet]. 2017 December [cited 2017 Dec i]. Available from: http://www.health.ri.gov/information/drugoverdoses/

-

Marshall BDL, Krieger MS, Yedinak JL, Ogera P, Banerjee P, Alexander-Scott NE, et al. Epidemiology of fentanyl-involved drug overdose deaths: a geospatial retrospective study in Rhode Island, USA. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:130–5.

-

Marshall BDL, Milloy One thousand-J, Wood Due east, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. Reduction in overdose bloodshed subsequently the opening of North America'south first medically supervised safer injecting facility: a retrospective population-based report. Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1429–37.

-

Hawk KF, Vaca Iron, D'Onofrio Thou. Reducing fatal opioid overdose: prevention, treatment and harm reduction strategies. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88(3):235–45.

-

Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, Quinn Due east, Doe-Simkins One thousand, Sorensen-Alawad A, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted fourth dimension serial analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174.

-

Wheeler Due east, Jones South, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ. Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons — United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2015;64(23):631–5.

-

Clark AK, Wilder CM, Winstanley EL. A systematic review of community opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs. J Addict Med. 2014;8(three):153–63.

-

Bury PO, Sullivan SD. Cost-effectiveness of distributing naloxone to heroin users for lay overdose reversal. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(1):1–nine.

-

Fairbairn N, Coffin PO, Walley AY. Naloxone for heroin, prescription opioid, and illicitly fabricated fentanyl overdoses: challenges and innovations responding to a dynamic epidemic. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:172–nine.

-

Burns G, DeRienz RT, Baker DD, Casavant M, Spiller HA. Could chest wall rigidity be a factor in rapid decease from illicit fentanyl corruption? Clin Toxicol. 2016;54(5):420–iii.

-

Somerville NJ, O'Donnell J, Gladden RM, Zibbell JE, Green TC, Younkin M, et al. Characteristics of fentanyl overdose - Massachusetts, 2014-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(14):382–six.

-

Poklis A. Fentanyl: a review for clinical and analytical toxicologists. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1995;33(5):439–47.

-

Amlani A, McKee G, Khamis N, Raghukumar 1000, Tsang E, Buxton JA. Why the FUSS (Fentanyl Urine Screen Study)? A cross-sectional survey to characterize an emerging threat to people who utilise drugs in British Columbia, Canada. Harm Reduct J. 2015;12:54.

-

Mema SC, Sage C, Popoff S, Bridgeman J, Taylor D, Corneil T. Expanding damage reduction to include fentanyl urine testing: results from a pilot in rural British Columbia. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):19.

-

Karamouzian Yard, Dohoo C, Forsting Southward, McNeil R, Kerr T, Lysyshyn M. Evaluation of a fentanyl drug checking service for clients of a supervised injection facility, Vancouver, Canada. Impairment Reduct J. 2018;15(1):46.

-

Brunt TM, Nagy C, Bücheli A, Martins D, Ugarte M, Beduwe C, et al. Drug testing in Europe: monitoring results of the Trans European Drug Information (TEDI) projection. Drug Test Anal. 2017;nine(two):188–98.

-

Sande M, Šabić South. The importance of drug checking outside the context of nightlife in Slovenia. Damage Reduct J. 2018;15(1):2.

-

Hungerbuehler I, Buecheli A, Schaub M. Drug Checking: a prevention measure for a heterogeneous group with high consumption frequency and polydrug use - evaluation of zurich's drug checking services. Damage Reduct J. 2011;eight:sixteen.

-

Kennedy MC, Scheim A, Rachlis B, Mitra S, Bardwell G, Rourke Due south, et al. Willingness to use drug checking within time to come supervised injection services among people who inject drugs in a mid-sized Canadian urban center. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:248–52.

-

Tupper KW, McCrae K, Garber I, Lysyshyn One thousand, Woods E. Initial results of a drug checking pilot programme to detect fentanyl adulteration in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;190:242–5.

-

Diep F. An off-label use of cheap strips—to examination for deadly contaminants in drugs—gets the backing of scientific discipline - Pacific Standard [Net]. Pacific Standard. 2018 [cited 2018 Jun 7]. Available from: https://psmag.com/social-justice/an-off-label-use-of-inexpensive-strips-to-examination-for-deadly-contaminants-in-drugs-gets-the-backing-of-science

-

Lysynshyn M, Dahoo C, Forsting Southward, Kerr T, McNeil R. Evaluation of a fentanyl drug checking program for clients of a supervised injection site. Vancouver: Canada. In University of British Columbia; 2017.

-

McGowan CR, Harris Chiliad, Platt L, Hope V, Rhodes T. Fentanyl cocky-testing outside supervised injection settings to prevent opioid overdose: do we know enough to promote it? Int J Drug Policy. 2018;58:31–6.

-

Peiper NC, Clarke SD, Vincent LB, Ciccarone D, Kral AH, Zibbell JE. Fentanyl exam strips as an opioid overdose prevention strategy: findings from a syringe services plan in the Southeastern Us. Int J Drug Policy [Internet]. 2018 Oct three; Bachelor from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.08.007

-

Bardwell G, Kerr T. Drug checking: a potential solution to the opioid overdose epidemic? Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2018;13(1):xx.

-

Wight P. Maine health advocates fence effectiveness of testing strips for fentanyl [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Jun seven]. Bachelor from: http://mainepublic.org/post/maine-health-advocates-contend-effectiveness-testing-strips-fentanyl

-

Davis Thou. Health department programme gives fentanyl testing kits to heroin users [Internet]. Seven Days. Vii Days; 2018 [cited 2018 Jun 7]. Available from: https://www.sevendaysvt.com/OffMessage/archives/2018/04/25/health-department-programme-gives-fentanyl-testing-kits-to-heroin-users

-

Karlamangla S. California is at present paying for people to test their drugs for fentanyl. Los Angeles Times [Internet]. 2018 May 31; Bachelor from: http://www.latimes.com/health/la-me-ln-fentanyl-test-strips-20180531-story.html

-

Serrano A. $1 fentanyl exam strip could be a major weapon against opioid ODs. Scientific American [Cyberspace]. 2018 Mar 8 [cited 2018 Jun 7]; Available from: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/1-fentanyl-test-strip-could-exist-a-major-weapon-against-opioid-ods/

-

Bebinger M. As fentanyl deaths rise, an off-label tool becomes a examination for the killer opioid. Wbur [Internet]. 2017 May xi [cited 2018 Mar 1]; Available from: http://www.wbur.org/commonhealth/2017/05/11/fentanyl-test-strips

-

McKnight C, Des Jarlais DC. Being "hooked up" during a sharp increase in the availability of illicitly manufactured fentanyl: adaptations of drug using practices amid people who use drugs (PWUD) in New York City. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;60:82–8.

-

Wayne Miller G. Fentanyl test strips latest tool in fight confronting fatal overdoses. Providence Journal [Internet]. 2018 Aug 31 [cited 2018 Sep 13]; Available from: http://www.providencejournal.com/news/20180831/fentanyl-examination-strips-latest-tool-in-fight-against-fatal-overdoses

-

Krieger MS, Yedinak JL, Buxton JA, Lysyshyn K, Bernstein E, Rich JD, et al. Loftier willingness to use rapid fentanyl test strips amidst young adults who use drugs. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):vii.

-

BTNX | Unmarried Drug Test Strip [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 February six]. Available from: https://www.btnx.com/Product?id=16940

-

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Fentanyl overdose reduction checking analysis study [internet]. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg Schoolhouse of Public Health; 2018 February. Available from: https://americanhealth.jhu.edu/sites/default/files/inlinefiles/Fentanyl_Executive_Summary_032018.pdf

-

Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane East. Demonstrating rigor using thematic assay: a hybrid arroyo of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):lxxx–92.

-

Crabtree BF, Miller WF. A template approach to text analysis: developing and using codebooks. In: Doing Qualitative Research. 1000 Oaks: SAGE Publishers; 1999.

-

Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and lawmaking development. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc; 1998.

-

Krieger MS, Goedel WC, Buxton JA, Lysyshyn M, Bernstein E, Sherman SG, et al. Utilise of rapid fentanyl test strips among immature adults who use drugs. Int J Drug Policy [Internet]. 2018 Oct 12; Available from: https://doi.org/x.1016/j.drugpo.2018.09.009

-

Hayashi Thou, Milloy Thousand-J, Lysyshyn One thousand, DeBeck Chiliad, Nosova E, Wood E, et al. Substance use patterns associated with recent exposure to fentanyl amongst people who inject drugs in Vancouver, Canada: a cross-sectional urine toxicology screening written report. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;183:1–6.

-

Kerr T, Mitra S, Kennedy MC, McNeil R. Supervised injection facilities in Canada: past, present, and future. Damage Reduct J. 2017;14(1):28.

-

Information Update - Health Canada is advising Canadians of the potential limitations when using test strips to observe fentanyl - Recalls and safety alerts [Internet]. Government of Canada. 2017 [cited 2018 May 25]. Available from: http://healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall-warning-rappel-avis/hc-sc/2017/65406a-eng.php?_ga=2.168019233.1667080909.1527266929-2134893241.1516990335

-

Harper Fifty, Powell J, Pijl EM. An overview of forensic drug testing methods and their suitability for harm reduction point-of-care services. Harm Reduct J. 2017;xiv(1):52.

-

Krug A, Hildebrand 1000, Sun N. "Nosotros don't need services. We have no problems": exploring the experiences of young people who inject drugs in accessing harm reduction services. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(ii(1)):i.

-

Lan C-Due west, Lin C, Thanh DC, Li L. Drug-related stigma and admission to care among people who inject drugs in Vietnam. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018;37(three):333–9.

-

Boucher LM, Marshall Z, Martin A, Larose-Hébert Thou, Flynn JV, Lalonde C, et al. Expanding conceptualizations of harm reduction: results from a qualitative community-based participatory research written report with people who inject drugs. Impairment Reduct J. 2017;14(ane):18.

-

Gowan T, Whetstone S, Andic T. Addiction, agency, and the politics of self-control: doing harm reduction in a heroin users' group. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(8):1251–60.

-

Mars SG, Bourgois P, Karandinos G, Montero F, Ciccarone D. "Every 'never' I ever said came truthful": transitions from opioid pills to heroin injecting. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(2):257–66.

-

Marshall Z, Dechman MK, Minichiello A, Alcock Fifty, Harris GE. Peering into the literature: a systematic review of the roles of people who inject drugs in harm reduction initiatives. Drug Booze Depend. 2015;151:1–14.

-

Des Jarlais DC, Nugent A, Solberg A, Freelemyer J, Mermin J, Holtzman D. Syringe service programs for persons who inject drugs in urban, suburban, and rural areas — U.s., 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2015;64(48):1337–41.

-

Figueroa C, Johnson C, Verster A, Baggaley R. Attitudes and acceptability on HIV self-testing among key populations: a literature review. AIDS Behav. 2015;xix(eleven):1949–65.

-

Katz DA, Golden MR, Hughes JP, Farquhar C, Stekler JD. HIV self-testing increases HIV testing frequency in loftier-risk men who have sex with men: a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;78(v):505–12.

-

Frasca T, Balan I, Ibitoye M, Valladares J, Dolezal C, Carballo-Diéguez A. Attitude and behavior changes among gay and bisexual men after employ of rapid abode HIV tests to screen sexual partners. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):950–7.

-

Myers JE, El-Sadr WM, Zerbe A, Branson BM. Rapid HIV self-testing: long in coming but opportunities beckon. AIDS. 2013;27(11):1687–95.

-

Dark-brown W tertiary, Carballo-Diéguez A, John RM, Schnall R. Information, motivation, and behavioral skills of loftier-chance young adults to use the HIV self-examination. AIDS Behav. 2016;xx(9):2000–9.

-

Lippman SA, Moran L, Sevelius J, Castillo LS, Ventura A, Treves-Kagan S, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of HIV self-testing among transgender women in San Francisco: a mixed methods pilot study. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(four):928–38.

-

Weiss NS, Rossing MA. Good for you screenee bias in epidemiologic studies of Cancer incidence. Epidemiology. 1996;7(3):319–22.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros would similar to give thanks the study participants for their contributions to the research. Nosotros would also like to thank Conor Millard, Giovannia Barbosa, and Esther Manu for their research support.

Funding

This pilot project was supported by Dark-brown University'southward Role of the Vice President for Enquiry through a Research Seed Grant. The report was likewise supported past the Brownish University Institutional Development Award, number U54GM115677 from the National Plant of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, which funds Advance Clinical and Translational Inquiry (Advance-CTR).

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on asking from the corresponding author, BDLM. The data are not publicly bachelor due to them containing data that could compromise research participant privacy/consent.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

JEG helped comport the surveys, drafted the manuscript, performed the quantitative analysis, and approved the final manuscript for submission. The qualitative coding was developed and performed by JEG, KMW, and KAP. JLY and BDLM conceived the pilot report and approved the final manuscript for submission. MSK and KMW helped revise the manuscript and help with the critical interpretations of the findings. BDLM planned the analyses and was the primary investigator of the airplane pilot study. All authors read and canonical the concluding manuscript.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Ideals approval and consent to participate

Our research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Brown University Part of Research Protections IRB, #1612001662. All participants provided written consent at the fourth dimension of the survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Publisher'due south Notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and point if changes were fabricated. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zilch/ane.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Nearly this commodity

Cite this article

Goldman, J.East., Waye, K.M., Periera, Chiliad.A. et al. Perspectives on rapid fentanyl exam strips as a harm reduction exercise among young adults who use drugs: a qualitative study. Harm Reduct J 16, 3 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-018-0276-0

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-018-0276-0

Keywords

- Overdose

- Opioids

- Fentanyl

- Damage reduction

- Rapid test

- Qualitative

harveymandivether.blogspot.com

Source: https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-018-0276-0

0 Response to "How Do You Know if Fenantyl Is in Your Drugs"

Post a Comment